Daily life after the war

Daily life after the war

During the period of rampant devaluation, wages were paid out daily because the money was worthless the next day. When my father came home from work, my mother was already waiting at the tram stop to take the wages and go straight to the shops where she would buy at least the essential groceries.

Childhood memories of the politician Hermann Barche (1913-2001)

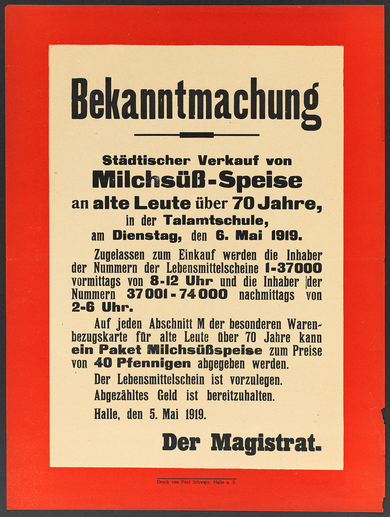

Contrary to what many hoped for, the economic situation only improved haltingly after the war. The command economy was initially upheld: food was still rationed (or was only available on the black market). It was not until the autumn of 1920 that meat, milk and potatoes were derationed, followed a little later by cereals.

Many companies had oriented their entire production towards the war. Now they had to switch to peace goods. The shortage of raw materials and the impoverishment of further strata of the population paralysed economic development. Returning soldiers increased the number of unemployed (despite introduction of the 48-hour week and short-time work in some cases). Large-scale state contracts were out of the question because of the high levels of debt. Rhineland occupation and territorial cessions disrupted established economic relations and made it necessary to provide for returnees as well as war refugees and victims. Added to this were the high reparation demands of the former wartime enemies.

Inflation had begun to rise even during the First World War. The ever-increasing pace of devaluation made life difficult for ordinary income earners. Although it had a favourable effect on exports and reduced internal government debt, many households lost their savings and thus some of their trust in the Republic. Soon, white and blue-collar workers were no longer paid monthly, but weekly, eventually even daily. Those who could, worked for food on farms or fed themselves from their allotments. Bartering flourished.

Only a currency reform in October/November 1923 offered some respite. The brief heyday of the "Golden Twenties" could begin.

Further information:

Michael Kunzel: Die Inflation. In: Lebendiges Museum Online, 06.07.2017

Arnulf Scriba: Hunger und soziales Elend. In: Lebendiges Museum Online, 06.07.2017