Food and raw material supply

Food and raw material supply

It has been suggested to me numerous times that a large number of the best pieces of clothing are being withheld from the general public by burying the dead in their finest clothes. That is very regrettable in light of the economic situation. […] It would be more practical to add the pieces to the communal used clothing points, where they can be restored for use by the civilian population. […] Feelings of reverence should not be hurt if the deceased are buried in garments made from paper weave, as industry is now certainly capable of manufacturing dignified clothing from paper weave for the purpose of burial.

Quoted from: Jens Flemming et. al., Lives in a State of Emergency. The Germans, Everyday Life, and the War 1914-1918, 2011

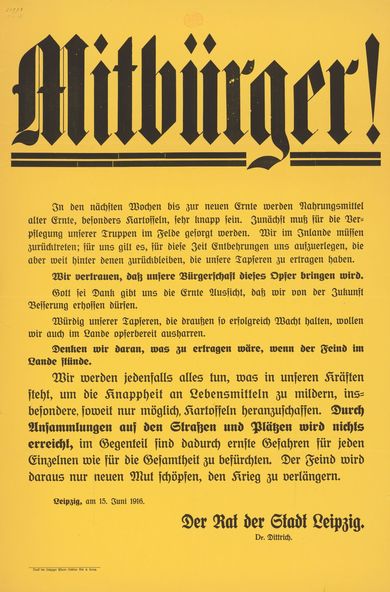

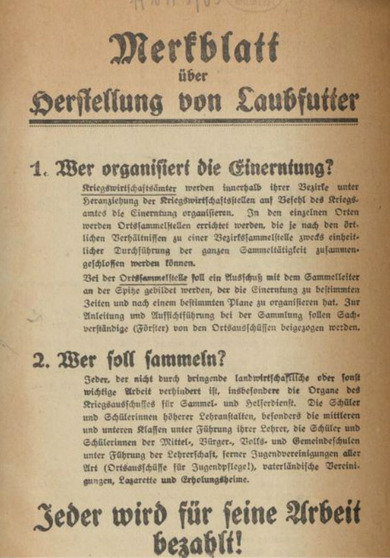

Due to the reorientation of industrial production towards the manufacture of war goods, the blockade of food imports and mistakes in food distribution, hunger became a serious problem for much of the civilian population, particularly in the second half of the war. The nutritional situation was especially dramatic in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and the German Reich, which had prepared poorly for a longer-term supply to the population. Here the weekly flour ration declined from 1,575 grams in 1915 to 1,400 grams in the final year of the war. During the same period, fat rations decreased from 100 grams to only 70 grams per week.

The climax of the supply crisis was in the winter of 1916/17, the Turnip Winter, when the average calorie value of the increasingly poor food was less than 1,000 calories per daily ration. Finally, from the spring of 1917, the first mass demonstrations were held against the desperate food situation and the ongoing war.

One of the administrative reactions to the crisis was the introduction in 1915 of the so-called war bread, which was baked from potato starch and other inferior types of flour. Milk was diluted with water, and substitutes were developed for many other products, which often resembled the original product only visually, but which no longer had any nutritional value.

Current estimates show that the malnutrition during the war cost the lives of around 800,000 people in the German Reich alone, mostly women, children and the elderly.